Are Retailers Paying Too Much for Their Extended Warranty Programs?

In order to maximize retail margins and customer loyalty in a post-COVID-19 world, retailers will need to reconsider every aspect of their operations, from floor planning, staff training, vendor management, and customer engagement strategies, to their extended warranty programs.

Editor's Note: This column, written by Mike Ryan of Consumer Priority

Service, is the latest in an ongoing series of contributed editorial

columns. Readers interested in authoring a contributed column in the

future can click here to see the Guidelines for Editorial Submissions page.

By Mike Ryan, senior vice president at Consumer Priority Service

As retailers emerge from COVID-19 isolation, many will find their business model turned upside down. Gone are the days (for now) of crowded showrooms full of customers testing gadgets, impulse buyers, and long checkout lines. Instead, expect to see social distancing measures such as scheduled appointments, contactless buying, and curbside pickups to become the norm. The impact is a reduction in overall transactions, resulting in declining gross revenues. Now more than ever, maximizing retailer margins on each customer transaction is critical.

In order to maximize margins and ensure sustainability, retailers would be served well if they use this time to reset and reconsider every aspect of their operations. Everything from floor planning, staff training, vendor management, and customer engagement strategies must be re-evaluated. More than ever, retailers must find new ways to attract and convert every potential customer while continuing to service and retain them for years to come.

We all remember the financial crisis of 2008-2009 and marvel at the resiliency of our retail partners. Few retailers would dispute the impact that their extended warranty program had on their ability to recover from the brink of potential bankruptcy.

Risk Management Structures Can Impact Retailer Profits

Similar to the recovery from the 2008-2009 financial crisis, retailers today could and should use extended warranty sales as a tool for recovery. After all, social distancing measures will provide sales associates with the opportunity to employ the consultative sales approach that they have always longed for.

At CPS, we believe that a consultative sales approach together with an increased focus on training will lead to increased extended warranty attachment rates. Attachment rates have long been an important Key Performance Indicator for every retailer and extended warranty provider, but how often do retailers consider if they are paying too much to their provider? And could they do better? The answer to these questions are found in the risk management structure of the retailers extended warranty program. Let's examine these structures to see what we can find out.

When launching an extended warranty program, retailers often rely upon a risk management structure suggested by their chosen service contract provider. Naturally, these providers negotiate with insurance companies to obtain the best financial structure for their business before they even approach a prospective retailer. Have you ever wondered why the cost of a program can vary dramatically from provider to provider? Isn't the actual risk of failure, on let's say a dishwasher, the same across all retailers? So why does the cost vary so much from provider to provider?

Know What Factors Determine Insurance Rates

Insurance companies set rates for programs based on historical loss data, if available, which is often not the case for new technologies, and other factors, including their internal expense ratios and desired profit margins. The desired profit margins are generally the same, usually 10%-20%, across all insurers, on a combined ratio (loss ratio plus expense ratio) basis. Internal expenses however, are dramatically different.

For example, if an insurer has a $1 billion advertising budget or uses artificial intelligence to predict weather patterns for CAT (catastrophic loss) exposures due to hurricanes, and happens to have a warranty practice as well; guess what? Part of those expenses are allocated to the warranty practice even though they do not use or benefit from those expenses. Ask anyone who files or reviews rate filings at an insurance department and they will tell you that there is no such thing as a "me too" rate filing because the expense portion of the rates cannot be the same across all insurers.

The Most Important Ratio

So, when a retailer asks a provider what loss ratio the program is priced at and they hear "85%," for example, does not mean the insurer is seeking a 15% profit? No, because an 85% loss ratio is only accounting for the risk portion of the rate; they haven't added the expense portion of the rate.

The more important ratio to examine is the combined ratio:

Combined Ratio = Incurred Losses + Expenses / Earned premiums

This means that an insurer with an expense ratio of 25% (most do) must have a loss ratio of 65% to achieve a desired profit of 10% on a combined ratio basis.

If the loss ratio were truly 85% in this example, that would mean the combined ratio for this program would be 110%. A program with a combined ratio of 110% will not last long at the current rates. The insurer will have to increase rates dramatically to overcome this deficit.

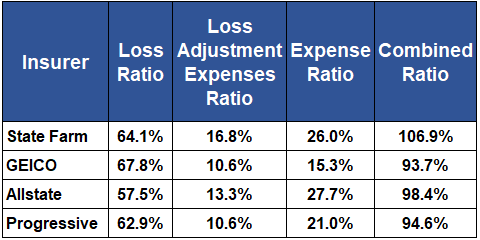

The chart below illustrates how the combined ratio impacts financial results and rates provided to retailers. In this example you can see that Geico has a loss ratio 10 points higher than Allstate, for example. However, Geico's combined ratio is 4.7 points lower than Allstate', 93.7% vs. 98.4%, because their expense ratios are lower.

Figure 1

Net Business Results for Top US Personal Auto Insurers

If these companies were competing for the same warranty business, Geico would be in a better position to provide lower rates for the program because of its 93.7% combined ratio, despite having the highest loss ratio of this entire group.

Earning Premiums

Added to this complexity of underwriting 1st dollar policies are premium earnings. Notice the C/R equation includes "earned premiums" in the denominator. Warranty contracts are longer in length than traditional insurance policies, they have manufacturer warranty periods, and losses occur in a variety of patterns.

Additionally, extended warranty contracts can be cancelled, often providing for a pro-rata refund of the unused portion of the contract, and they do not always have set exposure lengths. For example, when a product is repaired or replaced, the obligations under the contracts are often fulfilled; therefore, the loss exposure is eliminated from that point forward.

Insurers backing these contracts must have systems in place to delay or accelerate earnings of these contracts, according to the way losses actually occur, with methods other than pro-rata. The pro-rata earnings pattern earns an equal amount of premium each year or each month throughout the life of the contract.

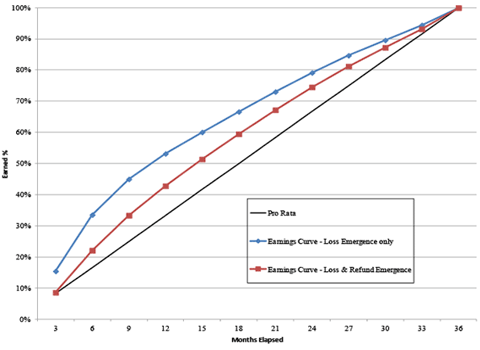

The rule of 78's method anticipates more losses occurring earlier in the contract life, while the reverse rule of 78's anticipates most losses occurring later in the contract life. This simple illustration demonstrates the problem with pro-rata earnings.

Figure 2

Cumulative Earnings Curve Comparison

Remember that the loss ratio at a given time is determined by using the formula:

LR = (losses due to claims + loss adjustment expense / total earned premium)

So, the more earned premium you have at a given point, the lower your loss ratio will be. In this example you can see that at month 24, the pro-rata method earns about 67% of the premium; whereas the other methods that use actual loss emergence & cancellations earns about 75% of the premium.

Insurers, unless they have proper systems in place, and they have actuaries that understand the extended warranty business, may incorrectly continue to account for any remaining premium for these contracts as unearned premium reserves (UPR) according to the earnings patterns their systems are programed to use, resulting in an inaccurate (higher) loss ratio at given points in time.

For more information on how UPR impacts loss ratios, click here: https://www.casact.org/pubs/forum/14fforum/Vaughan.pdf.

For more information earnings curves, click here: https://www.providers-administrators.com/348218/earnings-curves-matching-premium-with-losses-and-refunds.

Expense vs. Risk

Assuming they have considered these complexities and other factors an insurer will develop rates with a desired combined ratio in mind. The service contract provider adds their administrative fees to the insurance rates yielding what is known in the industry as a "dealer cost." The retailer then adds a desired margin to these costs, or accepts a suggested margin, usually 50%, offered by the service contract provider.

Together, these costs and margin percentage make up the retail cost of the extended warranty contract. Under this model, at least 50% of the contract price is related to costs, and even less related to the actual risk involved. Is there more profit available for retailers? Potentially, there is, if they are large enough and informed enough about alternative structures.

The automotive sector of the service contract industry does a great job navigating risk management structures, and advocating for themselves. Reinsurance, bonding, captives, excess of loss policies, and stop-loss insurance structures are common in the automotive sector. For varying reasons, the "brown & white" goods segment has largely failed to embrace the additional revenue opportunities relating to service contract underwriting structures.

Historical Practices Impact Costs

Why do the first dollar insurance model that uses a Contractual Liability or Service Contract Reimbursement policies dominate risk management structures within the brown & white sector of the service contract industry? Other more cost effective and proven compliance models exist that provide comparable protection to both customers and retailers. Moreover, these alternative models, which are approved by state regulators, provide greater program flexibility with the same underwriting diligence as their more expensive counterparts utilizing antiquated insurance policies as their means of compliance.

The Service Contract Model Act, versions of which have been adopted by nearly every state, sets out the financial responsibility requirements for Service Contract Providers. It states in part:

Section 3. C. In order to assure the faithful performance of a provider's obligations to its contract holders, each provider who is contractually obligated to provide service under a service contract shall:(1) Insure all service contracts under a reimbursement insurance policy issued by an insurer authorized to transact insurance in this state or;

(2) (a) Maintain a funded reserve account for its obligations under its contracts issued and outstanding in this state, and (b) Place in trust with the commissioner a financial security deposit, consisting of one of the following: (i) A surety bond issued by an authorized surety; (ii) Securities of the type eligible for deposit by authorized insurers in this state; (iii) Cash; (iv) A letter of credit issued by a qualified financial institution; or (v) Another form of security prescribed by regulations issued by the commissioner or;

(3) (a) Maintain a net worth of $100 million; and (b) Upon request, provide the Commissioner with a copy of the provider's or, if the provider's financial statements are consolidated with those of its parent company, the provider's parent company's most recent Form 10-K filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) within the last calendar year.

The full text of the Act can be found here: https://www.naic.org/store/free/MDL-685.pdf

Embracing Change

Clearly, based on the language of the statue, there are equally compliant structures available to retailers that can give them and their service contract providers more flexibility to develop distinct programs that will provide better pricing, faster speed to market, and therefore, higher profit margins. The notion that in order for a program to remain compliant, it must be insured with first dollar coverage from an insurer that happens to insure a particular provider is a fallacy.

In a post-COVID-19 world, retailers must embrace change to ensure their long term success. While there are many areas that retailers must re-evaluate to deliver long term profitability, the fastest to implement is a change to their service contract program. While CPS primarily offers first dollar coverage, we are not hamstrung by archaic methods of filing rates and forms like many of our competitors.

Furthermore, our ability to deploy flexible compliance models allows for less payments to middlemen and higher profits for retailers. By utilizing the far more cost effective programs offered through CPS, retailers can maximize their service contract profitability without sacrificing customer experience or their financial security.

About the Author

Mike Ryan has over 25 years of experience in the service contract industry, holding senior leadership positions in compliance, underwriting, product development, and sales and marketing at AIG, AmTrust, Starr Indemnity and Fortegra Financial. In his current role, Mr. Ryan is senior vice president of marketing and business development at Consumer Priority Service.

Consumer Priority Service (CPS) is a leader and disruptive innovator in the field of service plans. The company offers extended warranty coverage for virtually all types of consumer purchases, ranging from high-end consumer electronics, to computers, major appliances, power tools, lawn & garden equipment, and much more.

CPS delivers award winning service and is rated the number one service provider in its class. All plans are backed by an A.M. Best Rating of "A-" (Excellent) Insurance carrier. Learn more about CPS by visiting www.cpscentral.com. Apply today to join our executive sales team at www.cpscentral.com/jobs.aspx.