Swappable Battery Service Contracts:

Instead of wasting hours waiting for an electric car to recharge, why not design the vehicles to use swappable batteries? Though it may never be as quick as a NASCAR pit stop, it could take about as much time as pumping gas. And a new industry, based around the sale of energy in a rented "tank," could spread among dealerships, parts stores, and filling stations.

Why don't the automakers sell fuel for their vehicles? For more than a century, despite the obvious synergies, car manufacturers and filling stations have been run by completely separate companies. Throughout the era of gasoline and diesel, the vehicles and their fuel have been sold separately.

The practice doesn't seem to be rooted in law, as is the prohibition against car manufacturers owning their dealerships, or the century-ago breakup of the oil industry monopoly into several separate companies. It seems to be merely an unchallenged custom. But those unwritten rules may change, as the vehicles on the road move over to battery power.

Right now, electric car batteries are manufactured and sold separately from the electricity used to recharge them. That follows the present-day filling station model, where the manufacturer sells a vehicle with an empty tank, which the buyer then periodically refills with fuel.

But it doesn't have to be that way. Like the 20-pound propane tanks used for backyard barbecues, batteries can instead be rented, returned empty, and swapped for fully-charged units. It's the energy that is sold, with the battery merely its container. Imagine the filling station of the future: customers drive in, detach their empty battery, snap on a fully charged battery, and go on their way. Customers pay for the energy they need, through a service contract that guarantees them a supply of fully-charged battery modules.

Infrastructure Problems

There are two major barriers to such a scenario. First, car manufacturers have to make it as easy to swap batteries as backyard grill manufacturers have made it to exchange propane tanks, which is no easy task given the weight and size of a typical electric car battery. And second, the infrastructure of the automotive industry has to make room for swappable batteries in their shops. Either the manufacturers, the dealerships, the filling stations, or the auto parts retailers need to stock the rotable spares on their shelves.

In 2014, a team of engineers at the University of California, San Diego, converted a Volkswagen Golf into an electric car, mounting briefcase-size battery modules in the trunk, and swapping them out for fully-charged units as they were depleted. They called it the Modular Battery Exchange and Active Management system.

Figure 1

UCSD's Electric Car with Swappable Battery Modules

Source: Automotive News

That modular approach solved one problem: the sheer weight of the batteries and the difficulty of exchanging them. But it didn't solve the other problem: where to get the replenished modules while on the road?

Swappable Batteries

Currently, there doesn't seem to be any regulatory hurdle or antitrust law that prevents any of these companies from selling fuel. Anybody willing to comply with local fire codes, tax laws, and environmental regulations can sell gasoline or diesel. Supermarkets and department store chains sell fuel. Convenience stores and fast food restaurants sell fuel (or perhaps more precisely, filling stations have convenience stores and fast food restaurants on the premises). But car manufacturers and their franchise dealerships have largely stayed out of the petroleum-based fuel business.

In the U.S. we call them gas stations. In Britain they're petrol stations. In Germany, they're called Tankstellen, and the fuel they sell is called Benzin. Regular unleaded gasoline is called Magna in Mexico. Besides gasoline, most filling stations also sell diesel fuel, and some also sell alternative fuels such as ethanol and compressed natural gas. Some have even installed charging stations for electrical cars.

What they all have in common is that they sell a defined amount of energy for a defined amount of money. The pumps are metered. The tanks are filled, the batteries are recharged, and the sale is complete. But the filling stations don't sell the tanks, or in the case of electric cars, the batteries. Instead, they sell the energy that fills them.

It's not the government's fault that car manufacturers and their dealerships have largely stayed out of the fuel business. Governments write laws that define fuel efficiency, emissions standards, and even mandate the type and blend of fuel to be used. In the name of safety, governments also regulate the shape, size, and materials used to manufacture fuel tanks. Manufacturers comply with these laws. But manufacturers always sell just the tanks, not the energy that fills them. And dealerships sell the cars, not the fuel that runs them.

Think about the array of businesses involved with passenger cars. First, of course, there's the manufacturer, and the suppliers that work with that manufacturer. Next, there are the transportation companies that move those finished products from the factory to the dealership, by ship, train, or truck. Then of course there are the franchised dealerships that sell the cars to their customers.

Once the car is purchased, it typically needs both private insurance and a government registration and inspection of some kind. Once it's street-legal, it needs fuel. And in terms of upkeep and maintenance, it occasionally needs to be washed, repaired, tuned up, and to have its various fluids checked or changed.

While the vehicle is new, most repairs and some maintenance will be covered by a factory warranty and/or a pre-paid maintenance program. An extended warranty, mechanical breakdown insurance, or a vehicle service contract might also be purchased, prepaying for any needed repairs or replacements of covered items. And once all the factory warranties, roadside assistance plans, maintenance agreements, and service contracts have expired, the customer will have to pay for all repairs and maintenance out-of-pocket.

All the while, customers will have to buy fuel from companies that are separate from both the car manufacturer and the dealer. While most fuel retailers accept credit cards and fleet cards as well as cash, and some still accept personal checks, none sell any sort of service contracts to consumers that allow them to pre-pay for, say, a month's or a year's worth of fuel, all you can eat, in advance.

In many cities, you can buy an unlimited-ride ticket on a train or bus network for a day, week or month. But you cannot buy an unlimited fuel plan for a car. Instead, fuel is sold by the gallon, pay as you go, one tank at a time. Outside the U.S., the fuel is sold by the liter, and government taxes sometimes double or triple its price. But it's still sold based on volume, not on time or distance. You can't buy a week's worth of gas, or a hundred miles' worth of gas, though with some calculations you can buy enough gas to last a week or a hundred miles.

Keep-Out Laws

In the U.S., the leading car manufacturers and importers are companies such as General Motors, Toyota, Ford, Chrysler, Honda, Nissan, Volkswagen, BMW, and Hyundai. According to the National Automobile Dealers Association, their dealerships sold 17.5 million new cars last year, a new record.

NADA estimates that there are now 16,708 franchised auto dealers in the U.S. The largest new car dealership groups include Penske Automotive, Lithia Motors, AutoNation, Potamkin, Group 1 Automotive, and Sonic Automotive. But besides Tesla, there is no crossover between the list of manufacturers and the list of dealers.

It's abundantly clear why most automakers don't own the dealerships that sell their cars: that prohibition is written into U.S. state laws. In Texas, it's the Occupations Code, Title 14, Subtitle A, Chapter 2301 that prohibits a vehicle manufacturer from owning dealerships. In New York, it's the Franchised Motor Vehicle Dealer Act (2014 New York Vehicle & Traffic Laws, Title 4, Article 17-A) that prevents car manufacturers from owning dealerships. Similar laws exist in most other states.

But why don't car manufacturers or dealerships own and operate filling stations? And if there's a good reason for the separation, does it continue to make sense if the fuel being sold is electricity?

Battery-powered car manufacturers include Tesla, Nissan, BMW, Ford, and Volkswagen. In addition, Ford, Toyota and GM make plug-in hybrids that contain both gas engines and batteries. Several third-party companies such as ChargePoint and the Blink Network operate charging stations in strategic locations. Some even offer monthly subscriptions. Tesla operates an extensive network of charging stations for its customers. Plug-in charging stations are also available at some dealerships that sell electric vehicles. So in that sense, a network of battery recharge stations is already developing, led by the manufacturers, dealerships, and a new generation of filling stations.

Figure 2

Tesla's Supercharger Network

Source: Tesla Inc.

In 2016, American drivers consumed roughly 392 million gallons of gasoline per day, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. According to the National Association of Convenience Stores, there are now 123,807 retail shops selling motor fuels in the United States.

The leading gasoline brands in the U.S. are Exxon, Mobil, Shell, Gulf, Sunoco, Chevron, and BP. Chevron is one of the few major oil companies that continue to own and operate retail outlets. Most gas stations are now individually-owned franchises of one of these brands. Some also house charging stations, in specially-marked parking spots off to the side.

And of course there are the huge service centers and truck stops that have opened near the exits or right on the sides of major highways, featuring everything from tourist maps to hot showers. The always-open Iowa 80 truck stop near Davenport IA, in addition to having its own website, also contains a Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, Wendy's, Dairy Queen, Orange Julius, and a Caribou Coffee, not to mention a barber shop, dentist, and a chiropractor. Large retailers such as Costco, BJ's, Kroger, Sears, Tesco, and Walmart also frequently sell fuel in addition to food, apparel, housewares, and electronics.

In other countries, government-owned companies that own the oil drilling companies and distillers frequently also dominate the retail fuel sales business. For instance, Q8 is a subsidiary of the Kuwait Petroleum Corp. Statoil is majority-owned by the government of Norway. Pemex, Mexico's national oil company, is opening gas stations in Texas, complementing the near-monopoly it has with filling stations at home.

Meanwhile, the leading car parts retail chains are Advance Auto Parts, AutoZone, O'Reilly Automotive, Pep Boys, and the various independently-owned and company-owned NAPA AutoCare Centers. IBISWorld's Auto Parts Stores Industry Research Report estimates the U.S. market at $58 billion, employing 379,487 people in 63,737 businesses. Those four market-leading companies account for roughly 52% of the total, according to Warranty Week calculations.

In addition to selling parts backed by manufacturer's warranties, some of these retailers also issue product warranties for certain products they sell, such as batteries, brakes, and shocks. They accrue funds and they bear the risk of losses associated with the cost of warranty claims for these products. In other instances, manufacturers provide upfront allowances to the retailers in lieu of warranties. If claims exceed these allowances, the retailers must pay them.

Auto Parts Warranties

Warranty Week estimates that the top four companies paid roughly $175 million in product warranty claims last year, with O'Reilly, at nearly $74 million, at the top of the list. So they're experienced warranty professionals. And they already sell batteries. But they don't sell fuel or new cars. But they're still in a position to launch swappable battery services, if they're so inclined.

Notice that no companies make the list twice, being market leaders in car manufacturing, car sales, fuel sales, or retail parts sales. The gas-powered auto industry is very compartmentalized, for whatever reasons. Granted, some dealerships may also incidentally sell fuel or parts, and some gas stations may also incidentally sell vehicles, or be attached to used car lots. But there are no companies market-dominant in any two industry segments. They are manufacturers, dealerships, gas stations, or parts shops, but not multiples.

For instance, Longo Toyota, the world's busiest auto dealership (selling upwards of 22,000 vehicles per year), is so large that it houses on its 50-acre lot not one but two Enterprise car rental offices, in addition to a Starbucks cafe, a Subway restaurant, a Wells Fargo ATM, and a Verizon Wireless store. It even includes its own wheels and accessories shop, as well as a collision repair center, and its own four-story parking garage out back (with additional spaces on the roof).

But you know what it doesn't have? A gas station. The closest one is a Chevron station a half mile away. Ironically, there's an EVgo charging station across the street in the Nissan dealership. But there's no gas or diesel for sale within the site occupied by Longo Toyota.

In an era of gasoline and diesel, it probably makes perfect sense, for health and safety reasons, to separate the manufacture and sale of vehicles from the sale of flammable and even explosive fuels. But health and safety concerns don't explain gas station sushi. And it makes no sense to be concerned about health and safety when the fuel being sold is electricity that comes right off the grid. Electrocutions are still possible, but so is being struck by lightning.

Therefore it makes sense to expect that dealerships, gas stations, and possibly auto parts stores will all sell battery recharges. There are no technological, legal, or contractual barriers to entry. But will they also launch swappable battery services, if that market develops, like so many small local businesses that sell, rent, exchange, and refill propane tanks today?

Manufacturers are in control of the design decisions that would permit swappable batteries for electric cars. They might manufacture, sell, warrant and service the batteries themselves, or they might turn to suppliers. They might even turn to a competitor like Tesla, which is working with Panasonic to produce electric car batteries at their Gigafactory in Nevada. But they most certainly will have to design the removability of the batteries into their vehicles in the first place. If it's going to become feasible, it shouldn't be as complex as replacing a timing chain or head gasket. It has to be more simple and easy, like changing a tire or checking the oil.

The problem is that batteries large enough to power a passenger car weigh hundreds of pounds. The 24 kWh battery in the 2011 Nissan Leaf weighs 648 pounds (294 kg). The 33 kWh battery in the BMW i3 weighs 450 pounds (204 kg). And those are on the small end of the scale. The massive battery in the Tesla Model S weighs 1,200 pounds (540 kg). That is not the same as changing a spare tire, unless you're so strong that you don't need to use a jack.

By the way, in terms of comparisons, gasoline weighs in at about 6.3 pounds per gallon, while diesel weighs about 7.5 pounds. In other words, the fuel in a large passenger car can weigh as much as 126 pounds while a full tank in a semi truck can weigh as much as 2,250 pounds. However, to make an apples-to-apples comparison, we would also have to weigh the components replaced by the battery, including the engine and the fuel tank. Still, the heavy batteries are the reason a Tesla Model S can weigh as much as 4,941 pounds (2,246 kg).

Warranty Work

Passenger car manufacturers spent an estimated $48 billion worldwide last year on warranty claims, according to the July 6 edition of Warranty Week. Dealerships received most of that money, in return for the warranty work they performed on behalf of their customers. Retail parts shops and parts distributors also shared some of the wealth. On average, manufacturers ended up paying about 85% of the bill, and received reimbursements for the rest from their suppliers.

Dealers, of course, also sell most of the vehicle service contracts that consumers purchase. Last year, U.S. consumers spent roughly $17 billion on vehicle service contracts. Direct sales are only 5% of the industry, at most, according to research performed by Warranty Week in 2010. Out of the VSCs sold by dealers, roughly two-thirds are backed by third-party administrators and insurance companies, and one-third are administered and underwritten by affiliates of the manufacturer. So dealerships are both warranty and service contract experts.

But gas stations, and the fuel they sell, are largely outside the warranty chain that otherwise permeates the auto industry. We should note that all fuel products are subject to implied warranties of one sort or another, basically ensuring that they are suitable for a specified purpose. A filling station can't sell tap water and call it diesel fuel. If it fills a diesel car with mislabeled gasoline, it's liable for the engine damage it causes. But that's a civil lawsuit, not a warranty claim.

Some specially formulated fuels may be guaranteed to run cleaner or stop engine knocking. Some of the more dubious fuel additives might be blessed with magical protection properties. But even though these might be called product warranties, their distillers are not issuing written warranties or setting aside funds to pay claims. None of the top petroleum companies report any warranty reserves or accruals. So like their franchisees, they are also largely outside the warranty chain.

Repairs, meanwhile, are spread widely across the automotive industry. Most dealerships have service bays that provide repairs to customers, either customer-pay or warranty work. And then there are plenty of independently-owned gas stations that also have service bays that provide repair services. Most of it is customer-pay, but some of it is paid by vehicle service contract administrators.

Plus, there are plenty of retail outlets that sell tires, sound systems, batteries, security alarms, windows, mirrors, towing hitches, mud flaps, extra-loud horns, and many other types of component upgrades or replacements. Installation and basic repair services are virtual requirements for these lines of business. And then there are specialty shops that perform only oil changes, or only car washes. But they're frequently attached to convenience stores that sell food, drinks, and/or accessories.

In other words, the repair function in its broadest sense is also widely distributed across the industry. And having those service bays and all that lift equipment hanging around may help when it comes to deploying a battery-swapping infrastructure in the future. About the only group that doesn't provide repair services are the manufacturers themselves. They can't own dealerships and they don't sell fuel, and they don't operate standalone repair shops.

The Tesla Model

Tesla Inc. is changing that industry paradigm, upended the status quo in more ways than one. First, the manufacturer runs its own showrooms, which it calls retail galleries, and sells its cars online directly to the customer. It has fought somewhat successfully against state laws that prevent manufacturers from selling cars directly to consumers, bypassing independent dealerships. Tesla also operates a network of charging stations, and operates its own service centers, which perform all warranty work and most major repairs. One of the few independent third-party service providers in the mix is the network of Tesla Approved Body Shops, which deal with accidental damage.

Tesla's manufacturer's warranty protects the car for four years or 50,000 miles. In addition, the battery and drivetrain warranty protect those components for an additional four years (and unlimited distances for batteries made after 2015). That warranty also covers damage to a Tesla vehicle from a battery fire, even if it is the result of driver error.

If the owner lives or works within 15 miles of a Tesla Service Center, the company will send out a valet to retrieve the vehicle and bring it into the shop, and return it when the repairs are completed. If service is expected to take more than four hours, Tesla will provide either a loaner vehicle or a rental car.

Like most automakers, Tesla is also in the vehicle service contract business. In addition to two- and four-year protection plans, Tesla also sells three- and four-year maintenance plans, which include wheel alignments, fluid checks, and other routine inspections. Repairs and maintenance are also possible at third-party facilities, but Tesla makes keeping it all in-house a very appealing option. And those who go outside the network are liable to void their warranties if mistakes are made.

Speaking of keeping it all in-house, Tesla can also recommend local electricians who will install a 240-volt Wall Connector charging station and either a 60- or 90-amp circuit breaker in a customer's home. Such equipment will charge vehicles at an approximate rate of 52 miles of driving range per hour. Standard equipment, which plugs into regular 110-volt wall outlets, charges batteries at a rate of up to 29 miles of range per hour.

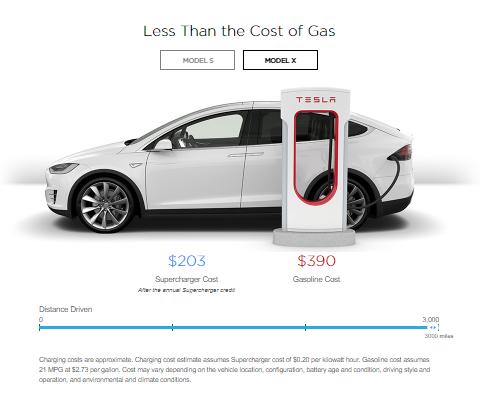

For longer road trips out of the local area, Tesla gives each Model S or Model X owner enough credits to use the facilities of its Supercharger network to drive about 1,000 miles per year for free. Additional recharges are customer-paid, though the cost is roughly half as much as gasoline would be per mile, assuming the electricity costs 20 cents per kilowatt-hour, the gas costs $2.73 per gallon, and the gas-powered car gets 21 miles to the gallon. In some states such as Oregon and Washington, the electricity at the Supercharger sites costs only 11 or 12 cents per kilowatt-hour. But in certain states, the Supercharger systems have an additional and optional slow speed, which can cost as little as 8 cents a minute.

Figure 3

Tesla's Gasoline vs. Electric Car Cost Comparison

Source: Tesla Inc.

The problem is, filling up will take at least half an hour at even the fastest Supercharger sites. Gasoline pumps, even at their slowest speed, can dispense at least five gallons per minute. And without getting lost in the details of volts, watts, and amps, suffice it to say that the amount of current required to make a battery recharge as fast as a gasoline or diesel fill-up would be the equivalent of the amount of power required to run thousands of washing machines -- millions of watts. Technological tricks can get that down to 15 minutes, but that's still more than twice as slow as the slowest gas pump.

Small vehicles have the same problem with wasted time. An electric scooter with 5 or 6 horsepower takes roughly two hours to store enough charge to provide 150 kilometers of range. The cost in money would be well under a dollar, but the cost in time is unacceptable if the customer is waiting to make food deliveries or transport packages. It helps that all the Supercharger stations have free Wi-Fi and are near cafes or restaurants. What else is there to do while you wait?

It would be much more efficient to mechanically swap a fully-charged battery for an empty one, and to then connect the trade-in to a charging station to get it ready for the next customer. Unfortunately, it's not as easy as popping new AA batteries into a flashlight. The units are large and heavy -- more analogous to the engines in gasoline cars than to the 12-volt batteries that start them.

NASCAR Pit Stops

However, as any NASCAR racing car fan can attest, vehicles can be designed in a way that facilitates ultra-fast pit stops. Some crews can change all four tires and refuel the vehicle in about 12 seconds. And in the airline industry, the concept of rotable spares keeps planes flying, instead of waiting on the ground for parts.

Just as Dell and HP made it possible for ordinary human beings to change their own PC hard drives, Tesla and other electric car manufacturers can design vehicles that use swappable batteries, as the company is rumored to be preparing to unveil for its Tesla Semi Truck, due to be launched next month.

Obviously, if the batteries weigh hundreds of pounds, they will have to be removed by some type of material handling platform. Ten years ago, an Israeli company called Better Place worked with Renault to create an infrastructure for electric cars with swappable batteries, but the venture ran out of cash and folded in 2012. Now, the torch passes to Tesla, which is designing swappable batteries into its electric truck.

For long-haul truck fleets, the Tesla Supercharger network provides an ideal infrastructure for battery swapping. The charging stations are deployed strategically at spaced intervals along major roads and highways, in shopping centers, near restaurants, in parking lots. There's one in Davenport, Iowa, about 16 miles east of the Iowa 80 truck stop, and there's another one being planned for West Covina, California, about five miles east of Longo Toyota.

The problem, once again, is time. Can a heavy battery be swapped in 5 to 10 minutes? Or better yet, what if it could be done as fast as a NASCAR tire change? What if you could pull in to a filling station, detach your empty battery, snap in a fully-charged battery, and be on your way in 12 seconds? And what if the cost of the energy still worked out to about half as much as either gasoline or diesel?

This lends itself to a service contract model. And by service contract, we don't mean an extended warranty, where the preferred outcome for both buyer and seller is non-usage. Industry estimates suggest that only one-in-three customers buys an extended warranty, and only one-in-ten of those buyers makes any use of it.

Smartphone Model?

What we mean by service contract is more akin to what the term means in the mobile phone industry. With mobile phones, many customers sign a one- or two-year service contract, which binds them to the carrier for that time period. They pay monthly, and while some service contracts still charge for minutes of airtime or gigabytes of data, many are flat-rate.

In the mobile phone industry, what others would call an extended warranty or a service contract is instead called mobile insurance or an equipment protection plan. They cover perils such as loss, theft, damage and defects, which may or may not occur. Google the phrase "mobile phone service contract" and you'll find nothing about protection plans.

On the commercial side of the service contract industry, which is where the Tesla truck will find its home, there are a variety of terms in use. But whether it's an agreement to repair a fleet of vehicles or all an office building's copy machines, usage is expected. It's not a question of "will my unit break?" It's more a question of how soon can it be repaired and how much will it cost. It's less a game of chance and more a means to prepay for the inevitable.

In the automotive industry, a swappable battery service contract might be sold by Tesla, Chevron, AutoNation, or perhaps by O'Reilly Automotive, entitling the buyer to one battery swap per week, using some sort of hand truck, hoist, pallet jack or forklift stacker, to remove the old battery and install a new one in 10 minutes. Clients wouldn't actually own the batteries. And they wouldn't really be renting them. Instead, their service contract would entitle them to 30, 60 or 90 kWh of power per week, provided they first return their depleted batteries, which would be recharged and given to the next customer.

In fact, this swappable battery model might work even better with smartphones, if new units were designed in such a way that the batteries could be snapped out and reinstalled in a few seconds. Imagine if all the retail outlets that sell smartphones and accessories also sold swappable batteries. Pop out the old one, and pop in the new one.

Once again, a service contract or some sort of club card could entitle its bearer to a set number of swaps per week. They wouldn't own the batteries, but they would be entitled to use all the energy stored in them.

If the industry could agree on some standard battery size and shape, as they have with C and D and AA and AAA, a new industry could be launched: smartphone battery swaps. But even if there were two or three or even four standard battery sizes, inventory management would not get out of hand.

So is this feasible? Can electric cars be designed to allow batteries to be rotated like tires? Will manufacturers, dealerships, filling stations, and auto parts retailers be willing to enter the business? And will consumers warm to the idea of buying battery service contracts rather than buying kilowatt-hours? Readers are welcome to send in your comments.