Warranty Software:

There's no heading in the software catalog for it, yet all manufacturers of warranted products have to use it. At Hewlett-Packard, two companies that don't even call themselves warranty software vendors are helping the company manage its warranty costs with analytical tools that weren't designed with warranty in mind.

When looking for warranty claims management software vendors, it quickly becomes apparent that not everything being used to analyze warranty claims is what one would call warranty software. Among the categories one would have to browse are business intelligence software, quality management software, and if one were in the automotive industry, dealership management software.

Warranty is perhaps the most overlooked and under-served $21 billion market in the whole economy. It's nothing more than a bullet-point feature for many of the enterprise resource planning and customer relationship management software suites now on the market.

Warranty is perhaps the most overlooked and under-served $21 billion market in the whole economy. It's nothing more than a bullet-point feature for many of the enterprise resource planning and customer relationship management software suites now on the market.

Look in the software catalogs for the warranty category. It's not there. Yet warranty costs can consume anywhere from 1% to 7% of most manufacturer's sales revenue. Reduce warranty claims or accruals at some companies by a single percentage point and you're already into the millions of dollars.

Last week, General Motors Corp. released its second quarter earnings statement. While net income was down sharply, at least the company was still in the black. Even the automotive sector of the company was in the black, but only after making a small 3% withdrawal from its warranty reserve fund. Without it, the automotive sector's $140 million net profit would have been a $59 million net loss. Analysts quickly jumped on this aspect of the bottom line, claiming it somehow tainted the "quality" of the company's earnings statement. But the point is, how many of the other bullet points besides warranty can make as dramatic a difference to a company's cost of sales and net profitability?

Warranty Software Vendors

So who's the biggest warranty software vendor of them all? Oracle is in some respects a warranty software vendor, in that its database systems process many of the records generated by warranty claims. SAP is a warranty software vendor. IBM is a warranty software vendor. Every major vendor of manufacturing software suites or packages is to some degree a warranty software vendor. But the biggest warranty software vendor of them all is perhaps Microsoft Corp., whose Excel spreadsheet is probably an icon on the desktop of every warranty administrator in the world. Why else would the federal government choose Excel as the one and only permissible format for TREAD Act reporting?

Of course, there are a handful of companies that focus rather exclusively on warranty claims management software. Indeed, one of them, Entigo Corp., is a sponsor of this publication. But even they must frequently partner with the big suite vendors, subcontracting just the warranty module on a much bigger manufacturing software project bid. Like warranty itself, a warranty software project must necessarily interact with numerous other functions and departments within a corporation. And for the most part, enterprise software buyers still prefer a generalist approach where their suites do everything fairly well to the specialist approach where one module really shines at one task.

It doesn't have to be this way. Small software companies that found the CRM and ERP booms to be busts are now courting manufacturers who turn out to be quite willing to discuss narrowly-focused real-world projects that can demonstrably cut product failure rates, improve customer satisfaction, boost a company's quality image, and oh, by the way, save millions of dollars in their first year of operation. But it takes a change of approach from one where warranty is seen as merely a cost to be managed -- a pile of paper that needs to be processed -- to one where warranty is seen as a wealth of data to be mined and exploited to a company's own benefit.

Business Intelligence Software

PolyVista Inc. is a business intelligence software company that quite accidentally now finds itself in the warranty business. Its largest customer turns out to be a Houston-based neighbor of theirs. Maybe you've heard of them? They used to be called Compaq Computer Corp., but now they're called the Personal Systems Group of Hewlett-Packard Co. They have a billion customers in 162 countries, and they're the third-largest warranty spender in the U.S., after GM and Ford.

PolyVista Inc. is a business intelligence software company that quite accidentally now finds itself in the warranty business. Its largest customer turns out to be a Houston-based neighbor of theirs. Maybe you've heard of them? They used to be called Compaq Computer Corp., but now they're called the Personal Systems Group of Hewlett-Packard Co. They have a billion customers in 162 countries, and they're the third-largest warranty spender in the U.S., after GM and Ford.

PolyVista came together two years ago, but its data mining and discovery technology was under development for a few years before that. The company markets a set of data analysis tools that quite generically can be pointed at a cash register's data to reveal buying patterns, such as how many supermarket customers buy milk and butter at the same time. Add to that some demographic data gleaned from a retailer's credit database, and PolyVista's tools can tell you how many college graduates in their 40s bought milk and butter at the same time last Friday afternoon.

Point those data analysis tools at a list of warranted parts replacements, however, and throw in some of the records collected by a company's call center, and they can tell you how many units failed during the first week of May in Montana, and how many of those failed components were repaired or replaced. They can list replacements by Zip Code, of if you prefer, chronologically by day and alphabetically by the last name of the service technician.

But report generation not what they do. Nor is it warranty claims analysis. Bob Ford, PolyVista's vice president of technology services, told Warranty Week that he still doesn't see warranty analysis as the company's core business, even though its prime customer uses the software for that purpose. "What we do see is a vertical solution space that includes warranty analysis," he said. "We believe PolyVista's technology can be applied very successfully in this space. And we believe it can be applicable in any warranty situation, whether it be it cars or dishwashers."

Others undoubtedly agree. In early June, the data warehousing magazine DM Review, a publication of Thomson Media, announced the winners of their 2003 World Class Solution Awards competition. At the top of the list in the business intelligence category was PolyVista, recognized for their installation at HP's PSG center in Houston.

Early on, PolyVista chose to develop their product around OLAP, the On-Line Analytical Processing model developed ten years ago by the late Dr. Edgar Codd, who had earlier invented the relational database model.

Data Mining and Warranty Analysis

Ford said OLAP is like a high-performance shovel, in that it can tear into data and return results fast. "But it didn't tell you where to dig," he said. OLAP helps find patterns and anomalies in the data, but first someone has to build an algorithm to process the data and then someone has to point it at the data. PolyVista went about developing those tools, which allow average users to construct and run analyses of their data from their own computer consoles.

Competitors in the business intelligence marketplace were targeting their analytics tools at the statisticians and what Ford called "the brilliant people" in the top echelons of an enterprise. PolyVista instead focused on the supervisors and the line managers and the people closer to the production.

"We thought there had to be something there in the middle," Ford said, between the high-end statisticians with access to the high-end stats packages, and the guys doing range sorts and cell formulae on their Excel spreadsheets.

"We started with Compaq in Houston," Ford said. Why not? At the time, PolyVista was a Houston startup, and Compaq was one of that city's most important manufacturers. PolyVista was originally brought in on a customer satisfaction data analysis bid that slowly morphed into the warranty analysis contract it has now with HP.

PolyVista was introduced to the project by a consulting company called Suma Partners Ltd., which was bidding on a Web dashboard development project that would have all sorts of knobs and dials and displays on it measuring customer satisfaction levels. A consultant with Suma brought along PolyVista to make a presentation about its data analysis tools that were aimed at people a few levels down from the data analysts.

"So we teamed up on this RFP," Ford continued. At first, PolyVista was looking at call center records, trying to make some sense of the data for Compaq, so that it could improve its customer satisfaction levels. And of course call center data has a high correlation with warranty claims data, so PolyVista started looking at that database too. They quickly realized that customer satisfaction levels and warranty costs have an inverse relationship: the more was spent on warranty, the higher the satisfaction ratings. The more cost-cutting on warranty, the lower satisfaction levels.

"We truly believed that if we could merge their call center data with their warranty parts data, that we could get a head start on identifying areas that are beginning to see problems, and relate that back to both service and part requests, and track how particular models were doing," Ford said. "So we pitched to them was an analytical solution moreso than a visual dashboard solution."

It pitched to them the algorithms it developed for data mining, which could reveal anomalies and patterns in the data that might not be discovered using other tools. And it showed to them "the cube," a split-screen interface it developed, where the analyst could chose something from the top quadrant and something from the bottom quadrant to see what relationship could be displayed in another quadrant.

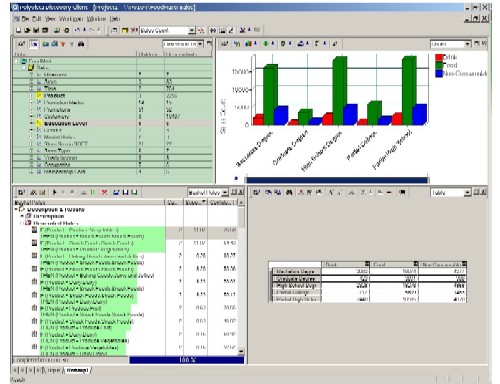

The PolyVista Interface

Though the wording isn't too visible on the above diagram (click on it to open a full-sized image in another browser window), the olive green quadrant in the upper left contains the summary demographic data about customers of a theoretical supermarket named FoodMart. In the lower left are rules for correlations between different products purchased by those customers. On the right is an analysis of customers' education level in graphical form at the top, and in spreadsheet form at the bottom. It's not exactly a Web dashboard, and it's shaped more like a rectangle than a cube, but it does function as a console of sorts for non-experts who want to poke around the data, looking for patterns or anomalies.

In a manufacturing example, the available data might include model numbers and plants where products were assembled, plus detains on what parts suppliers supplied which plants by the day, week, or month. There also might be data on complaints and problems reported to the company's call center by customers, and perhaps financial, sales, or demographic data on those customers. Ford said a user can pick a handful of statistics, and ask the system to look for anomalies in that data, and report back a top 50 list of unusual occurrences, scored by their deviance from the norm. Once such a result is found, the user can examine the data that produced it by drilling down into that quadrant of the screen, and decide what actions need to be taken to fix the problem.

Change the upper left quadrant to call center data and the lower left to computer parts data, and you essentially have the system PolyVista was demonstrating for Compaq. So that the Compaq people who would use the system could practice using the OLAP tools interactively, PolyVista decided to put on some tutorials of its system for the folks in Houston.

Teaching by Example

At one such session, Ford explained to the class how he could find "interesting intersections" in their parts data, such as how he found that 80% of the time a modem was replaced in a particular unit, the keyboard also was replaced; but how only 30% of the time that a keyboard was replaced was a modem also involved. And he showed Compaq employees by example how they themselves could use PolyVista as an OLAP browser, constructing their own data cubes and looking for their own correlations.

At one such session, Ford explained to the class how he could find "interesting intersections" in their parts data, such as how he found that 80% of the time a modem was replaced in a particular unit, the keyboard also was replaced; but how only 30% of the time that a keyboard was replaced was a modem also involved. And he showed Compaq employees by example how they themselves could use PolyVista as an OLAP browser, constructing their own data cubes and looking for their own correlations.

"Somebody in the room knew the business," Ford recounted. "And he said, 'Bob, look at the model number. Those are laptops. In order to replace the modem, you have to go through the keyboard.'" They correctly surmised that perhaps the service techs in the field were damaging the keyboards while replacing the modems. And after the class was over, they used the system to narrow it down to one service provider who was doing much of the keyboard damaging. His students asked their design engineers to look into changing the mounting of the keyboard, and asked their product people to distribute better instructions on how to remove keyboards without damaging them. All from an example in an instruction class.

An earlier episode where somebody saw something that wasn't there is perhaps the only reason that PolyVista got into Compaq in the first place. At a presentation where PolyVista was trying to explain how its technology could be the dashboard they wanted, a Compaq employee and staff fellow by the name of John Landry realized that the data mining and discovery technology on view was what they actually needed.

"When John Landry came in halfway through our presentation, he sat in the back and never said a word," Ford said. "When it was all over, he basically helped this group rewrite their objective. Needless to say, we won the RFP. And it was largely due to his vision, of something more than just a better warranty system and better tracking of customer satisfaction, of bringing discovery analytics to real-time use at HP."

Landry has a slightly different memory of the meeting. "There were two efforts going on," he told Warranty Week. "One was trying to put together a system where we could put information in front of the management team about what's happening with their warranty expenses -- an executive 'dashboard' kind of thing."

"I actually started a project in conjunction with that [dashboard effort]," Landry said. He was the technology leader on the second team, which was looking for analytical tools that could be useful to the warranty people a few rungs down the corporate ladder from the executive-level people who would get the dashboard interface. "I was working with the same team, but what I was going after was actionable information that could be used by the people that can really impact the warranty -- not the high-level executives, but the people that work the day-to-day jobs."

Wanted: Real-Time Data

The second team wanted access to information on a daily basis, not weekly or monthly as the executives did. Landry said he figures that the first month after a new product ships is the most crucial time. In those first 30 days, a product begins to shows its personality, so that if a recurring problem is detected early enough, its correction will have a major impact on the whole product life cycle. And the earlier a problem is found, the more money can be saved long-term on warranty expense.

"We were looking for technology that could help us get the information in the hands of engineers and product developers, because that's where the real impact is on lowering your warranty expense -- you just eliminate the event altogether." Landry's team determined that PolyVista was the wrong company for the dashboard contract, but they realized the startup could provide exactly what they were seeking for their analytics project.

"We thought we'd have to build this from the ground up," he said. "We didn't think there was anything out there."

There were plenty of business analytics tools available, but they were aimed at a fairly high-end operator: the data analyst. Such a person might be a genius at data manipulation and reporting, but they probably didn't know much about quality control, reliability, or warranty claims management, not to mention the actual products being manufactured by Compaq. And even if they did, they certainly weren't geared up for the daily kinds of probes and explorations that the project team had in mind.

"The real breakthrough is that information has to flow freely in a way that's useful for the people that can use it," Landry said.

The HP Merger

So while one team continued with and eventually abandoned the dashboard console concept, the second team sat down with PolyVista and talked about how their tools could be adapted so they could be 'driven' by somebody much closer to the production line. That meeting took place just a few short months before the plan for a merger between Compaq and HP was announced in Sept. 2001. Most projects came to a screeching stop.

"It was actually in the middle of our evaluation, during a 90-day pilot, came the word about this merger," Ford said. But while many projects then in progress were put on hold by the merger, PolyVista's was not. "They wanted to continue the pilot, because it was proving to be very successful. But they couldn't make any commitments..."

"It was actually in the middle of our evaluation, during a 90-day pilot, came the word about this merger," Ford said. But while many projects then in progress were put on hold by the merger, PolyVista's was not. "They wanted to continue the pilot, because it was proving to be very successful. But they couldn't make any commitments..."

PolyVista spent a total of 18 months on-site, navigating along with Landry's team through the merger process. But in the end it came out with a signed license deal. After the merger was completed in May 2002, PolyVista's tools found a home within HP's Personal Systems Group, which is where most of Compaq's lines of business ended up. But it also has since made inroads in non-Compaq corners of PSG, as well as to other segments of HP's business such as the Imaging and Printing Group and the Enterprise Systems Group.

The impact has been dramatic, and the payback was almost immediate. "Once we turned PolyVista onto our call data, it immediately popped out to us that we had a serious problem with some modems in our desktops on the consumer side." Landry said the call centers were reporting frequent and recurring problems with the modems being unable to detect a dial tone.

Landry said the product people were somewhat skeptical that some magical software package could spot such a problem. "The thing that was always difficult in the past was we could go and say, 'Product Team, we have this problem.' But they would never believe you. We had no credibility."

"So instead of putting together a presentation, we sat them down in front of the tool, and we showed it to them," Landry said. Once they performed the same analyses and reached the same conclusion, the product team commented that they too had a credibility gap when it came time to convince their suppliers that there was a problem. So they brought in the modem supplier and sat them down in front of the same tools. Same result.

They could look at the data half a dozen ways -- examining the age of the modem, the place it was made, or the number of days after shipment that elapsed before the customer reported the problem. The product team was convinced; the supplier was convinced; and the problem was fixed.

"Immediately, we saw the impact, because we're looking at daily data," Landry said. "But we ended up getting rid of that supplier anyway."

HP estimated what the cost of fixing that modem problem would have been in the field rather than on the production line, and found that the PolyVista tools helped it save $2 to $3 million just on that one case. In another instance, the daily data helped HP quickly detect a startup problem that affected every copy of the then-brand-new Windows XP operating system. HP contacted Microsoft, which developed a fix that HP mailed out to early buyers but which more importantly was incorporated into its not-yet-shipped units.

Landry said now people frequently call him with formerly off-the-wall questions -- how many LCD screens in laptops failed on a sunny day last week in Florida? "I just go pull up the cube, look in it, and tell them what I see. Then they go make a decision in a meeting right then and there, based upon what I told them."

Other Vistas to Explore

So where will PolyVista go next? To date, most of its customers have been close to home, including First Choice Medical Management, Service Corp. International, and soon, the MD Anderson Cancer Center. As the company spreads out from its Houston base, Ford sees an easy jump from HP to other computer manufacturers and perhaps into telecom and electronics. What matters more to PolyVista than the industry of its next prospect is the complexity of its prospect's product line. Where PolyVista would do best, Ford said, would be in situations where the final assembled product contains multiple components from multiple sources/locations and in multiple configurations -- could be the description of either a car or a computer. But not a garden tool or desk chair. "If you're building a three-component product, and the only thing that breaks is one of these three things in any combination, then I would say you don't need PolyVista to discover anything. You've probably got it covered some other way."

Another corner of Hewlett-Packard uses yet another vendor's data analysis tools for warranty analysis. And as with PolyVista, that company doesn't really see itself as a warranty software vendor. ReliaSoft Corp., based in Tucson, Arizona, sells a Web-based portal system called the Quality Tracking and Management System. Though it's aimed more squarely at failure analysis, this system inevitably analyzes warranty claims as well. But its scope also includes product design and development work, aimed at improving the quality and reliability of the product before, within, and after its warranty period, with the emphasis on before.

Reliability Software

Doug Ogden, vice president of ReliaSoft, noted that the company takes its name from the words reliability and software. "In a much broader scope, we supply software to reliability engineers, which would encompass warranty analysis amongst many other things," Ogden said. He said warranty claims are simply a way to measure the reliability of a product once it's in the field. But quality and reliability are best managed in the factory, before products reach the hands of customers.

It's not warranty software, but it does perform warranty analysis. It's not exclusive to the computer industry, yet it is used by units within many of the major computer manufacturers. So while it might not make a list of warranty software vendors, customers such as Hewlett-Packard, Dell Inc., Cisco Systems Inc., 3Com Corp., Sun Microsystems, Maxtor Corp., Applied Materials, Seagate Technology., EMC Corp., Xerox, Western Digital, Quantum and Storage Technology use the company's software for warranty analysis. But analyzing failures and predicting warranty costs are just features of the much broader product -- not its defining category.

In its quarterly corporate newsletter, ReliaSoft wrote the following: "Accurate predictions about the quantity of products that will be returned under warranty can provide huge benefits to manufacturing organizations. Among other advantages, better warranty data analysis allows an organization to make the most efficient allocation of resources to warranty services provision. Likewise, they allow the manufacturer to anticipate customer support needs and take the necessary steps to insure customer satisfaction with the warranty process. Warranty data analysis can also provide a valuable early-warning signal to the manufacturer when there is a serious product quality problem in the field, which gives the organization time to mobilize its resources to meet the challenge before serious financial, legal or other problems occur."

Avoiding Warranty Costs

"How do you avoid warranty costs? It's a piece of reliability engineering," Ogden said. "It's an important piece, but I'm not sure if it's the number one piece. I think your failure analysis during the design process is probably more important. However, if you don't do that properly, then you start looking at warranty claims."

ReliaSoft sells QTMS as its enterprise package, plus a set of a la carte tools such as the Weibull++ package, which are aimed at the power user who needs to predict such items as failure rates and warranty costs along with numerous other aspects of product lifecycle analysis. Click on the ReliaSoft screen shot below to see a case study on the use of Weibull++ in warranty analysis.

Within the warranty space, these are early warning systems for manufacturers of any stripe, sounding the alarm when actuals climb above predicted rates. "We would look at not just warranty costs, but why they're occurring," Ogden said. "What are the failure modes in the product? How can that be improved? How can the product be designed better to eliminate some of those warranty costs?"

Most of the company's customers are in the electronics and automotive industries, with one of the biggest being Hewlett-Packard, Ogden said. ReliaSoft supplied a QTMS system to the huge HP Imaging and Printing Group located in Corvallis, Oregon. IPG uses it as an early warning system for their line of inkjet printers, tracking warranted product defects and feeding that information back to the production line. But they also use it for much more even before the printer gets put in a box and shipped off to a dealership.

Like PolyVista, the ReliaSoft system merges call center data with product returns, and reports back to the production people in more or less real time. But Ogden hasn't heard of PolyVista, and Bob Ford hasn't heard of ReliaSoft. Even within Hewlett-Packard, there are probably few people that know about both these warranty analysis systems within the company. But then again, why would they? Both are designed to be used close to the production lines, by the people most directly involved with manufacturing and assembly. If both groups do their jobs right, there will never be any crisis to report in to headquarters.